US Interest Rates Are Falling. Is There Anything We Can Do? – Center for Retirement Research

Policies being tried by countries like Sweden may prevent the fertility rate from falling further.

The declining birth rate is an important development, not only in the US but around the world. Some praise the trend as an example of women’s ability to control their own destiny; others criticized it as an economic disaster. Regardless of one’s views, at current fertility rates, the world’s population is expected to peak in the 2060s and then begin to decline, which may not be such a good thing.

In the US, interest rates have generally been declining since the end of the baby boom in the mid-1960s, and that decline accelerated after the Great Depression. Many observers thought that once the economy recovered, the fertility rate would rise again. Apparently, it didn’t happen (see Figure 1). To me, this is not a surprise. My colleague Angie Chen and I found in 2018 that inflation can be explained by underlying factors — specifically, women’s education and income growth — that may not have changed. In 2023, the fertility rate was 1.62, a very low number and below what was needed to maintain the current population.

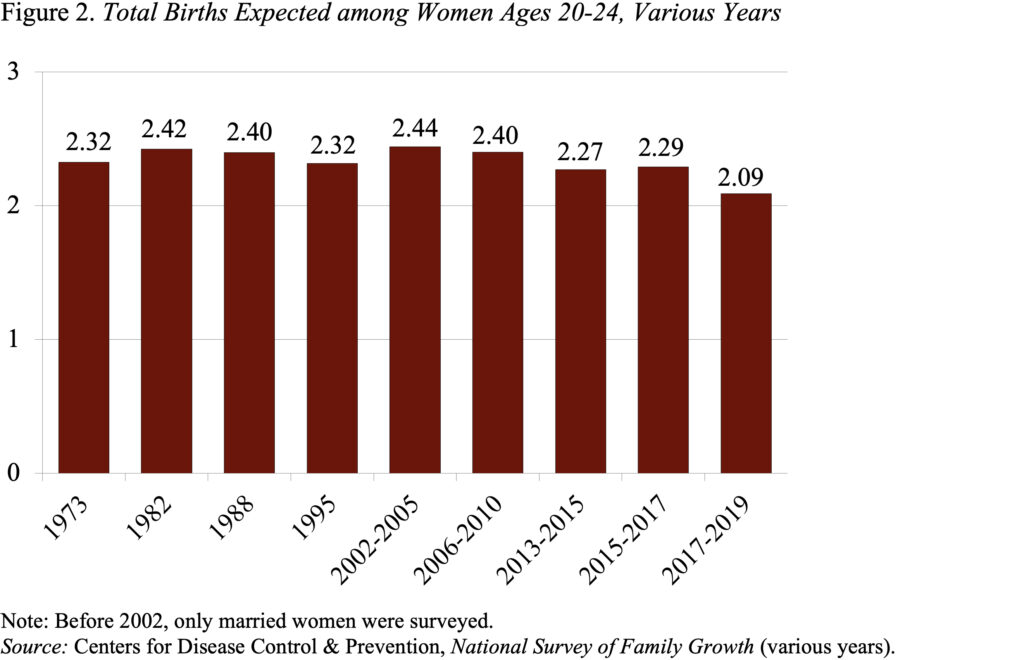

Interestingly, survey data suggest that women in their 20s still expect to have more than two children (see Figure 2), although fewer than in previous surveys. A large gap between expectation and birth means that something makes parenting difficult. It is clear that people marry later; in 2023, the median age of first marriage for women was 28 – almost 6 years later than in the early 1980s. Parents-to-be may want to reach other important milestones before having a child, such as paying off student loans or buying a house. That makes sense given the high cost of childcare.

All these problems seem to be very American, however, so I was interested in what was happening in other countries, where government policies are more generous. I was particularly interested in Sweden, where the government seems to have done everything possible to help new families.

- Parental Leave: 480 days per child, each parent is entitled to 240 days.

- Financial Support: For the first 390 days, compensation is based on the parent’s income up to a cap, and for the remaining 90 days, a fixed amount (about $17) per day.

- Flexible Work Arrangements: When returning to work, parents may reduce their hours to 75 percent or more until the child turns eight.

- Sick Child Leave: Parents are entitled to up to 120 days of sick leave per child per year.

- Childcare and Preschool: Subsidized childcare and free preschool from one to six.

- Universal Healthcare: Maternal care and child health services are free.

- Education: Free primary, secondary and higher education.

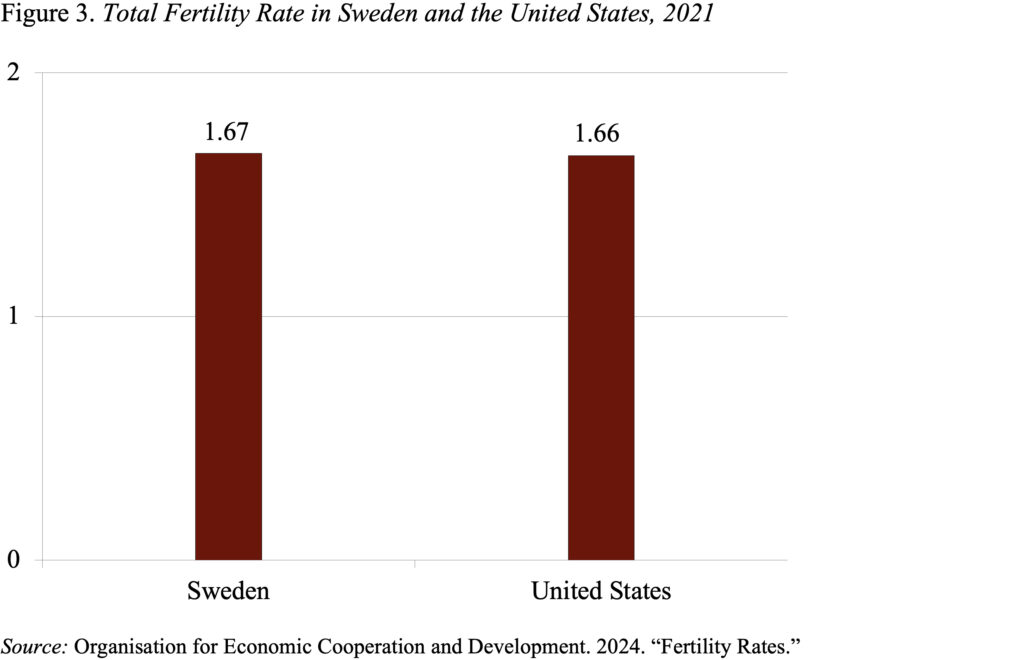

All of these arrangements sound attractive compared to the US; parents bear almost no financial costs associated with having children, and the workplace appears to be more profitable. So how do Sweden’s fertility rates compare to those in the US? The data for 2021 shows that they are the same (see Figure 3).

That identity does not mean that Sweden has bought nothing with its generous parental policies. Since 2000 – when many of these policies were introduced – Sweden’s fertility rate increased from 1.55 to 1.67, while the rate in the US decreased from 2.06 to 1.66. Furthermore, the participation rate of women in Sweden is 88 percent compared to only 75 percent in the US.

The Swedish results suggest that it is very difficult for the government to increase the fertility rate. That said, we can try to make it easier for women to work and have children. Such efforts may prevent the fertility rate from falling further.

Source link