Medicaid Is Crucial to Older Americans, But Can It Handle a Rapidly Aging Population? – Center for Retirement Research

Needs may not be met or heavy burdens may fall on families.

Medicaid is the nation’s publicly funded long-term care program for low-income people. It was originally established to provide benefits to those receiving cash assistance or “welfare.” In the case of older Americans, that source of cash benefits was – and remains – the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. However, over the years, Congress and the states have expanded Medicaid to reach the vast majority of uninsured Americans who live near or below the poverty level.

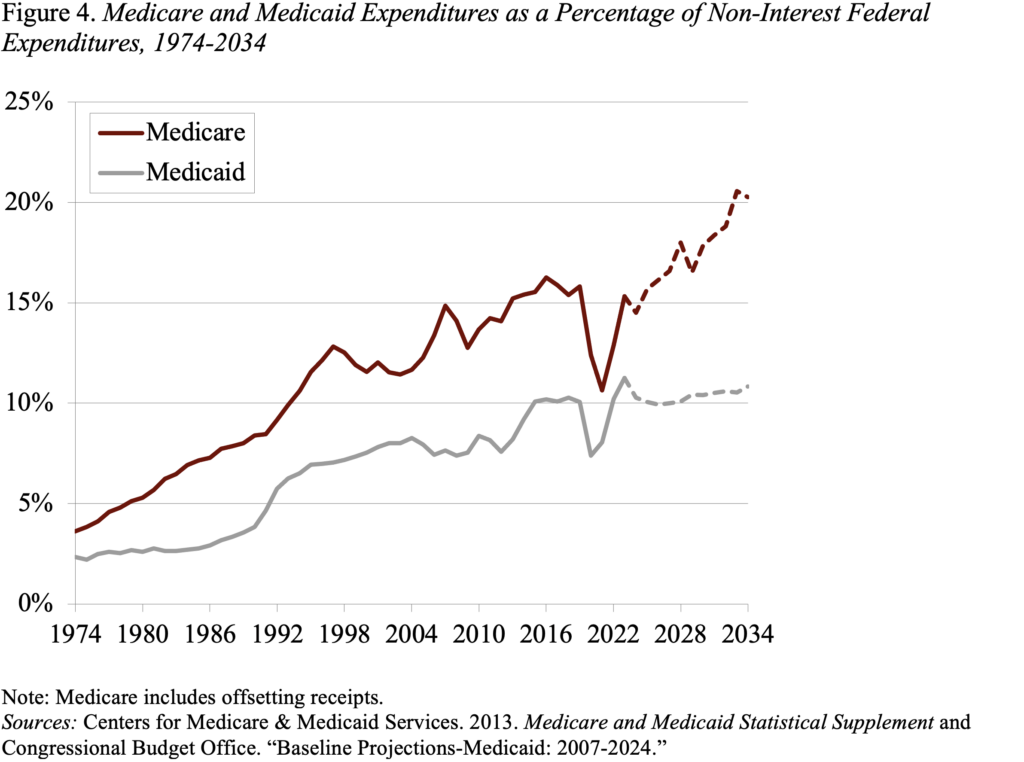

Medicaid is funded jointly by local and state governments. The federal government sets certain basic requirements, but states have the flexibility to design their own versions of Medicaid within the basic framework of federal law. Spending on Medicaid has grown significantly over time as a percentage of GDP and as a percentage of federal and state budgets.

Trying to understand Medicaid actually boggles my mind. It is complex with an array of complex pathways to benefits. But, it turns out that Medicaid is a really important program for those 65+.

Medicaid provides benefits to five major low-income groups – children, seniors (under age 65) in families, seniors (under age 65) without children covered under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), people with disabilities, and individuals who are eligible based on age (65+). According to the most recent data available – 2021 – the 65+ age group accounted for 10 percent of beneficiaries and 20 percent of spending (see Figure 1).

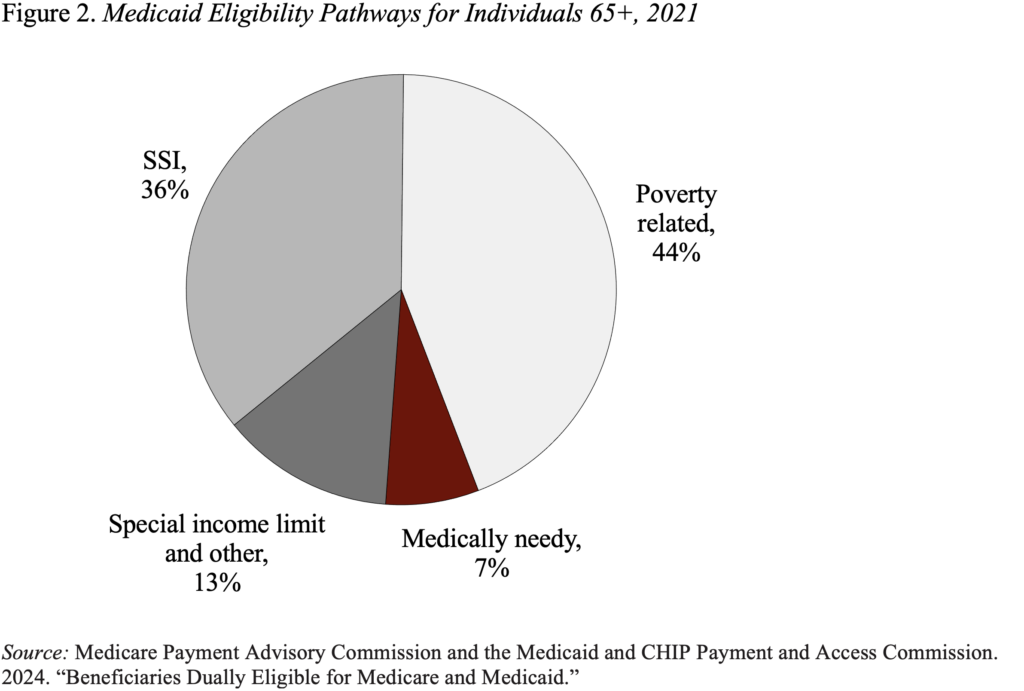

Within the Age 65+ group, Medicaid beneficiaries can be classified as “very needy” and “medically needy.” As shown in Figure 2, most Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in the most needy means – SSI, Special Income Limit, or Poverty Related.

Medicaid offers two major types of benefits for those age 65+. The first – for both those eligible through SSI and poverty-related means – is the Medicare Savings Programs to cover some or all of their Medicare out-of-pocket costs. Additionally, counties are allowed to provide special assistance to people who need long-term services and supports, including nursing home care. One route to these benefits — offered by 42 states — is the “special income rule,” which allows people with incomes up to 300 percent of the SSI limits to qualify for benefits. In 2004, the maximum monthly SSI benefit is $943 per month for a single person and $1,415 for a couple, which is 75 percent of the federal poverty level. SSI beneficiaries are also subject to asset limits of $2,000 for individuals and $3,000 for couples.

Some states also expand Medicaid to “medically needy” individuals. Recipients must also have assets subject to limits that vary by state but, under the basic rules, are generally the same as SSI asset limits. The income test, however, is the net income for out-of-pocket medical expenses. Not all states offer this option, and the medically indigent make up only 7 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries age 65+.

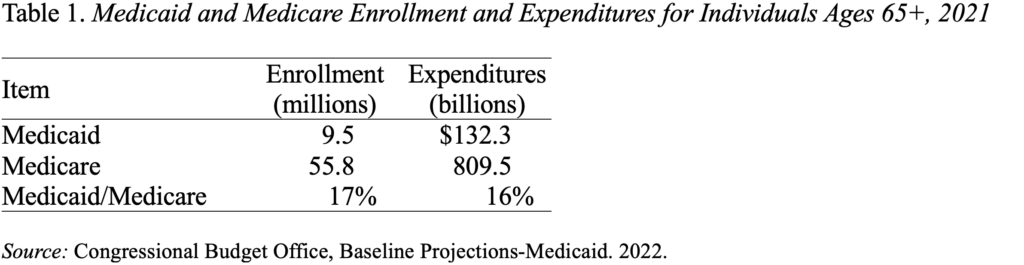

To get some idea of the importance of Medicaid for retirees, Table 1 compares the enrollment and costs of those 65+ under both Medicaid and Medicare. According to both metrics, Medicaid accounts for 16-17 percent of Medicare’s value.

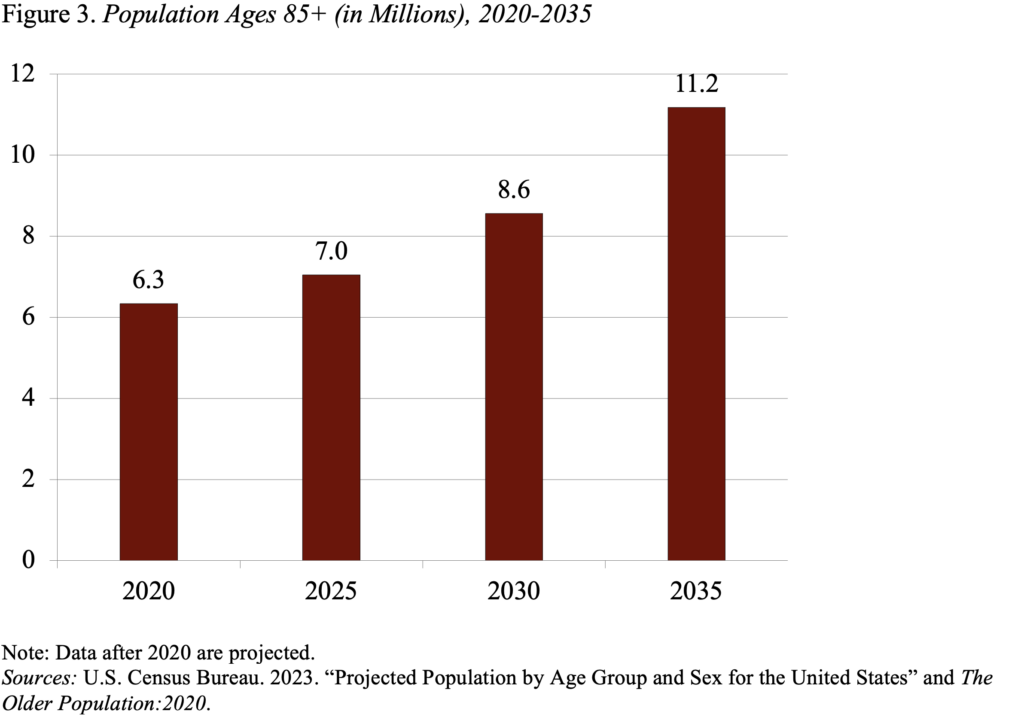

A more important question is what Medicaid spending looks like in the future, as the number of people 85 + – the group with the greatest long-term care needs – is expected to increase from about 7 million today to 11 million in 2035 (see Figure 3).

The Congressional Budget Office projects that Medicaid – unlike Medicare – is scheduled to hold 10 percent of federal non-interest expenditures (see Figure 4). For those age 65+, the project projects an increase of only 1 million compared to an increase of 4 million for those 85+ and only a modest increase in enrollment costs per enrollment – perhaps reflecting room and board savings as care moves from care. services in private homes.

The bottom line, however, is that, despite the aging population, Medicaid is not destined to play a bigger role in the future than it does today. The flipside of financial constraints can be unmet needs or a greater burden on families.

Source link